Written November 10th , 1986

Source: Son of Roger V. Foehringer

These are the adventures or misadventures of Cpl. Roger V. Foehringer,

Serial #15317417, U.S. Army. The story really begins in the early part of

December 1942. The place was Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. The

football season had just ended, but that seemed insignificant considering what

was going on at the time. World War II was in full swing and the draft board was

breathing down my neck. As a result, on one of the first weekends in December,

a group of guys from Xavier decided to go downtown to the city hall to enlist in

the Navy Air Corp. So off we went to downtown Cincinnati, the Fountain Square

and the old Post Office…City Hall and the Navy Recruiting Office. After we

signed in, the first thing on the agenda as far as they were concerned was our

health.

They took us on the various rounds with the first stop being a long narrow

room where the Officer there had all of us stand against the wall while the man at

the head of the line read an eye chart at the other end of the room. While the Officer was doing that, a corpsman was moving along the line looking in our ears,

nose and throat.

When he came to me, he examined my ears and after he did, he asked

me to step to the other side of the room, which I did.

When they completed the eye examination for the seven or eight men in

my group, the corpsman said to me, “I want you to talk to the recruiting officer”.

He motioned for me to follow and led me down the hall to the office of the Naval

Recruiting Officer. He talked to the Officer for a few minutes in private and then

said “Goodbye” to me.

“Sit down Roger I want to talk to you.” The Officer said. So I sat down

and he said, “From the Corpsman’s examination we believe you have recently

suffered a concussion which has resulted in a triangle tear of your eardrum.” The

Officer went on. “I know that you played football this year at Xavier and it

probably happened this fall while you were playing. I’m not going to ask you to

believe me as you probably don’t, so I’m going to call over to the clinic that

Xavier uses for the athletes and have them take a look for us.”

The clinic was known as the Decorsi Clinic, located in downtown

Cincinnati not far from the City Hall where I was. The Officer called and made an

appointment for me to go over immediately to be examined by one of the doctors

over there. I went over to the clinic and was immediately ushered into a Doctor’s

office, an eye, ear, nose, throat specialist. After examining my ears, he

confirmed exactly what the Corpsman from the Navy had already told me. He

went on to tell me that there was no way the Navy or Army would ever accept me

into military service with this perforated puncture of the eardrum. This kind of

made me a little non-plussed, I didn’t know what to do.

The following week there was another group of the guys in our R.O.T.C.

program going over to Fort Thomas in Kentucky to enlist in the Army Reserve

Corps. I said, “Let’s try it again” and over I went in a six by six with a bunch of

my buddies from Xavier R.O.T.C. to Ft. Thomas, across the Ohio River. We got

there and of course the first procedure when we got there was a physical

examination. In this case there were about ten or twelve of us and we were

asked to strip and were then moved from point to point, Doctors examining each

man. I finally came to the eyes, ears and nose area. I didn’t say anything to the

Doctor as he examined my eyes and ears. When he completed his exam, but

didn’t say a word. At that point I couldn’t tell if I had passed or not, but I sure

wasn’t going to say anything.

We moved along to the next positions and finally all of the physical exams

were completed. We were all told we had passed and that we had been

accepted in the Army Reserve Corps. They also told us we would be called up to

active duty in the relatively near future, but at what time they could not tell us… it

could be a couple of weeks…it could be a month…it could be four or five months.

So back to Xavier we went.

The University rushed our whole collegiate year as fast as they could

since they knew we would be going into the service very shortly.

I believe we finished our first year sometime near the end of March; it was

a very speedy year. I still had not been called up to active duty so I headed back

to Chicago and my family. I decided to just sweat it out until the enlisted reserve

corps called me up to active duty. I was already in the service but not on active

duty.

After a few weeks went by and they still hadn’t called so I got a job

working in a laundry. June of 1943, which was almost six months after I had

enlisted I got the call. It was December 13 th , 1942 when I enlisted at Ft. Thomas,

Kentucky and here it was June of 1943 that they were calling me to active duty. I

was to suppose to report to Camp Grant outside of Rockford, Illinois, which I did

around June 12 th .

Once I arrived they gave me a battery of intelligence tests from which they

decided I should continue with my 105 Howitzer training I had started in the

R.O.T.C. program at Xavier.

However before I could be transferred, the baseball coach at Camp Grant,

a man by the name of Bob Eiden said he wanted me to stay and play hardball for

the Camp Grant baseball team. It was not unusual in those days for each camp

throughout the country to have various sports programs, football, baseball, etc.

for the entertainment of the rest of the troops, probably morale builders also.

I went over and tried out for the team and made it as a second baseman.

For approximately ten days I stayed, then it became annoying that I wasn’t really

going to be doing any fighting. I was always going to be left behind and never

see any of the action of the war. So I requested to be transferred to Ft. Sill,

Oklahoma, where my buddies who had gone into Service with me had been sent

two weeks previously.

There I rejoined a goodly number of the R.O.T.C. enlistees from Xavier

University. They had just started their basic training so I hadn’t missed much.

We took the seventeen weeks of basic training there at Ft. Sill and on the

last day of the training I was advised along with another chap that we would not

be shipping out with the rest of our buddies as we were going to be given an

option on some other programs that the Army had in store for us. The rest of our

buddies were given a 10-day delay en route furlough and told to report to Ft.

Meade, Maryland P.O.E. (Port of Embarkation). They were going to go overseas

undoubtedly to Europe.

This other chap, who was from Salt Lake City, and myself were called in

individually to the Commanding Officer’s and given the option of going overseas

with our buddies, going to Infantry Officer’s Candidate school at Ft. Benning, GA.

or going to a program I never heard of called the “Army Specialized Training

Program”. I asked what the program was and they told me that it meant going

back to college. The army would send me back to College and educate me with

an Engineering Degree. That sounded very good to me so I accepted it. As you

can see my “Gung Ho” attitude no longer haunted me. The Army wasn’t what I

thought it was going to be and this “Army Specialized Training Program” looked

like a way for me to continue to get an education and not have to put up with the

Army.

They sent me to the University of Arkansas, at Fayetteville, Arkansas.

There were about 25 men from various parts of the country in the Freshman

Class I was in, that came there to join in the program. We continued on this

program at the University for approximately six months. Then the Army

disbanded the program saying that they needed men for active duty. We were

sent to Camp Maxie, Texas to join and become part of the 99 th Infantry Division.

They were going to give us another seventeen weeks basic training as

infantrymen. We would then be assigned to individual Companies as part of this

Infantry Div.

So once again I went through seventeen weeks of basic training, this time

in the infantry and again on the last day I was called over the loudspeaker

system and told to report to the orderly room, which I did. They told me that I

should get my gear together, a jeep would pick me up in a half hour and I was

being transferred to the 924 th Field Artillery Battalion. Needless to say I was very

happy, because believe me when I say the infantry is really a dog’s life. Because

the rules and regulations would not permit anyone to hold any rank if they were

back at college under the A.S.T.F. program, I was still only a private, so I was at

the bottom of the barrel as usual with the 924 th Field Artillery Battalion Service

Battery.

My Commander was a Captain Cobb from Arkansas. Many of the men in

this unit, which numbered about 80, were from the South. Some of them, which

was very hard for me to believe, didn’t know how to read or write. It was the first

time I had ever run into anything like that.

This was an entirely white unit; there had been no integration in the

Services at this time. My Captain though he was not much of an athlete himself

really loved baseball. One day I made a couple of sterling plays. One in

particular, I was playing left field and ran back with my back to the infield and

caught a very long, hard hit ball over my head, “a la Willie Mays”. When I came

in to the bench after the inning was over, Captain Cobb came up to me and said,

“You just made PFC with that catch, I will notify the First Sergeant of your new

rating”. So there I was in athletics again and just made PFC. That meant a

grand total of $4.00 extra a month, making it fifty four bucks I was being paid for

each month I was in Service. Since I’m talking about pay I might as well tell you

that out of that $54.00 dollars a month came $18.75 for a war bond, $6.50 for my

G.I. insurance and $6.50 for my laundry. When I lined up to get paid and they

always paid us in cash, at the end of the month, I’d get a grand total of about

$15.00 to $16.00 dollars.

Finally in early September of 1944, I was given a 10-day furlough knowing

full well that when I came back we would be shipped overseas. And, that’s

exactly what happened. About the middle of September we were sent to a Port

of Embarkation, called Camp Miles Standish, near Boston, Massachusetts, then

we were shipped in a big troop convoy. There must have been 50 or 60 ships in

this convoy and I can recall destroyer escorts racing in and around us at times

when we were on alert to German submarine activity.

It took us fourteen days of rough weather to get to Greenock, Scotland in

the Firth of Clyde. By far the majority of the men were seasick. I was fortunate,

my stomach never caused me a problem whatsoever, in fact, they put me on KP

in the kitchen. As far as I was concerned the trip really was not that bad and we

had a lot of free time.

After we had landed in Greenock, we went overboard on cargo nets down

onto tenders that were bobbing up and down along side our troop transport. The

tender took us to the little town of Greenock, then we were taken to the railroad

station and put aboard cars, regular passenger cars. At a later date you’ll note

why I make this distinction of regular passenger cars.

We then spent the next 24 hours going from Greenock all the way down to

Plymouth and Weymouth in southern England on the channel coast.

Then an interesting thing occurred, a letter from my folks caught up with

me while at the small camp outside Weymouth, England. When my mother

wrote that I had relatives in the London area, well that was the only requirement

in order to get a pass to go to London, if you had relatives and could prove it. So

I was able to take that letter to the First Sergeant’s office and get a pass to go

into London.

It really wasn’t that much fun because I was the alone and didn’t have any

friends or buddies to go with me. Nevertheless I took the train from Weymouth

up to London, contacted the Red Cross at Charing Cross Station. They assigned

me to an apartment building they had transformed into billets for servicemen on

leave such as me.

The most interesting thing I saw that weekend in London was the damage

that had been done by the German buzz bombs and V2 rocket bombs. How

these people had suffered. Distruction, block after block, that had taken place

two or three years before I got there, these people had been suffering a long

time, that’s for sure.

While I was there I also tried to meet a friend, Burt Gardner. We were

supposed to meet under “Big Ben”, what I didn’t know at the time was, “Big Ben”

was a whole city block square.

Just a few days after I got back, the 924 th Field Artillery was put on small

LCT’s. These ships…these Landing Craft would hold a 6×6 Army Truck, a 105

Howitzer and about 50 troops. It was a flat-bottomed type of craft that we were

taking across the English Channel from Weymouth to Le Harve, France. There

were many of these small craft making the crossing. We landed in Le Harve on

what was a very wide, sandy and rocky beach. We didn’t land at a pier or dock,

but on the beach. Our 6×6 got stuck in the sand, but was pulled out by wreckers

that were lined up on the beach for just that very purpose.

We were on our way up to the Front Line, the beginning of the Allied drive

through France. I remember bivouacking in our truck along the road and having

French peasants, farm people coming up and talking to us.

I had taken four years of French and thought I could speak it fluently. My

first engagement with a French farm person, I realized we were talking two

different languages. My French was Parisian and theirs was from the country.

We could converse, but not very well. It was like an Irishman speaking pig Latin

to them I’m sure. It was certainly very embarrassing because my buddies

expected me to “Parle Vous France” excellent, but I just didn’t have it.

When we got to the front it was very stable. There was a “No Man’s Land”

and each of the participants were sending patrols through, normally at night. But

no large-scale attacks were planned. It was like we were settling in for the winter

right on the German-Belgian border.

We had gone through the towns of Liege, Namur and Verviers in Belgium

and a small town with a camp called Elsenborn.

The winter had set in and it was cold and snowy. Although I was not

suffering from the weather since I was the Artillery, with a 105 Howitzer outfit and

not with the Infantry, we had a warm bed. In fact, I picked up a fold away cot out

of an old Belgian farmhouse, threw it onto the 6×6 and took it with me wherever I

went. I had a bed to sleep on in the abandoned houses that we took over as we

moved on day by day.

My first sight of a buddy killed in action was really a fluke. He was with his

group in their 6 by 6 and they were strafed by a German fighter plane. They had

baled out of their truck and into a ditch but apparently it was his time and that

was it. A very small piece of shrapnel struck him right square in the middle of the

head. There was no other mark on him whatsoever, he was killed instantly. I’m

trying to remember his name, he was very tall, 6ft. 3ins. or so, young Polish boy

from Cicero. I want to say his name, I believe it was Milt Pappel. That was when

the reality of the war struck home for the first time, seeing my first dead buddy.

It was in the early days of December 1944, probably the 1 st , 2 nd or 3 rd day

of December. It was snowing, making it difficult for us to drive and get our

supplies to the 105 gun batteries. We were bringing up their food and

ammunition daily. One of the big items we supplied was gasoline, brought in

what were called, “gerry cans”, on our six by six. We also brought water…very

important.

Periodically I was asked to go out with a forward observer party. I along

with a Forward Observer Officer, Artillery Officer and a Radioman with a pack

radio, a jeep driver and a squad of infantry would go through the lines, which

were fixed and booby-trapped. We’d go through at night, stay until the next day

and radio back German positions to our Artillery units for their fire missions.

Then we would come back in through the lines. I only did this a couple of times

and it really scared the hell out of me.

Many times you were all by yourself and didn’t know which way was

home. But, I did get back safe and sound, it seemed like our little group never

did get ambushed and had no serious problem.

All and all my duties were not very awe inspiring, I had a warm bed just

about every night and I had good hot food every day, so it wasn’t bad at all,

never suspected what was about to happen.

I can look back now and say it should never have happened. We should

have been prepared, we knew the Germans had changed troops in front of us

and that something was up and something was going to happen shortly.

It’s now the middle of December sometime around the 14 th to 16 th and the

odyssey continues. I’m recording this now on a snowy day, November 20 th , 1986

it has been snowing here in Ellwood Greens for the past several hours with an

accumulation of about 2 inches, reminding me of those days in December of

1944 right on the Belgian-German border.

I was on guard duty that night, the 16 th , we had billeted in a farmhouse on

the outskirts of a town by the name of Bulligen in Belgium. The house was a

combination home and barn. The barn was connected to the house at the rear.

We were all comfortably setup in the house. My guard duty tour was for

four hours, I believe it was from midnight until 4 AM. Sometime during the night

a group of M8 scout cars from a cavalry reconnaissance unit pulled down the

road to the farm. They were all excited and told us that the Germans had broken

through somewhere east of us and that they themselves were trying to get out of

there. I notified the Captain Cobb of this news and he in turn alerted the troops.

He called Division Headquarters and was told that we should dig in on either side

of this small farm road that cut through the hilly countryside.

Nearby there was a number of planes parked on a grassy area, just off the

side of this road on a landing field for the Piper Cub Field Artillery Observation

planes.

Seems kind of funny when I look back at it now, but my guard duty was

over at 4A.M. and I went back to the farmhouse, climbed back in to my sack to

get some rest. I was awakened at approximately 7o’clock and told that we were

digging in. We were supposed to take the machine guns off our 6×6, move them

up a small hill and set up some type of resistance to the German advance.

We were not advised exactly what type of German troops were coming

our way or that there were tanks. Much of the preparation, that is digging the

holes for the mounts of the machine guns, had taken place while I was sleeping

during the night.

A Corporal grabbed me and another guy and told us we were to take a

case of grenades up the hill to one of the machine gun positions which was on

the north side of the road near the top of the hill. The three of us, another PFC,

the Corporal and myself, started along the road and up the hill. I was on the left

hand side holding one handle of the case of grenades and the other PFC was

holding the right handle of the grenade case with the Corporal next to him.

We had not reached a point where we could see over the hill, when down

upon us came a German Tiger tank. As I said previously this was a small farm

road and on the left side, the side that I was on, was lined with a row of hedges,

to the right was level ground, the Air Field where the Piper Cubs were. Needless

to say I didn’t have stage fright, I jumped over, through and around the

hedgerow. While doing so, I lost my M1 Carbine, my helmet and tore my field

jacket, but apparently made it safely to the other side. The German tankers must

have been as surprised as we were, since they didn’t immediately shoot at us.

Whne they did the only shots that were fired at me were machine gun bursts over

my head, through the hedgerow.

I lay there flat on the ground right at the base of the bushes and the next

tank went by completely missing me. The next vehicle that came by was a half-

track with infantry loaded in the back. There must have been ten or twelve

German infantrymen. There was a slight pause in the firing and that was my time

to break away from the road, through the snow, out to the farm field, the snow

was fairly heavy out in the field.

In order to get away from the activity of the road, I kept on a perpendicular

course until I was several hundred yards from the road and the Germans. Then I

turned and went back toward the village of Bulligen, and the farmhouse where I

had stayed the night before and where I had last seen the other troops from my

outfit.

There is no feeling like being alone, unarmed and having the hell scared

out of you and not know exactly what the hell to do. This was my position and

my thinking as I turned the corner of the barn connected to the farmhouse.

When I rounded the corner, a blast, which at the time I thought was from

machine gun or rifle bullets or some other type of weapon that had hit me full

blast. I hit the ground, then crept and crawled into the barn which was full of hay.

As I lay on the ground feeling my arms, legs, nose, ears, my whole body, to see

where I was hit. I just knew I had to have been shot, but there was no blood and

no pain.

As I chanced a quick glance out of the barn, in came running one of my

buddies, a PFC like myself by the name of Al Goldstein, a Jewish boy from

Detroit, Michigan. It seems he had just fired a bazooka and he was coming in

with a bazooka to re-load it with another rocket that he was carrying. I then

realized what had hit me; it had been the backlash of the bazooka rather than a

machine gun or another weapon. But it sure felt like I had a hole in me the size

of that bazooka, yet I hadn’t been touched.

I helped Al load the thing and crawled back out with him. His first rocket

had gone over the top of the tank which had stopped on the road just out in front

of the farm house where we were hiding. The shell had hit the wall of another

farm the other side of the road. This time when he fired the rocket it again went

right over the top of the tank, Al was obviously firing too high. At this point the

tank crew must have gotten a little excited, as they gunned up the motor and

started swinging the turret towards our position. Al and I got inside the

farmhouse as fast as we could.

In the farmhouse there were some other GI’s including the cooks of our

service battery. A couple of us found some carbines in the farm house and went

up to the upper story of the farm house and looked out through the back window

which was the direction the Germans were coming from. This would be towards

the East and we could see the Germans had fanned out on the field that I had

just crossed. Although I couldn’t see it at the time I crossed, the Germans had

taken the machine gun nest that we had dug in on the hill, the one we had

planned on supplying with grenades.

We broke the windows and started to fire at these troops. They were just

sitting out there in front of us…it was really easy shooting. But before very long

we could hear the rumble of a tank. The farmhouse began to shake and we all

decided that the “Better Side of Valor” was to hide. We got out of the second

story and down into the basement of the farmhouse. We busted up the carbines

so that nobody else could use them. The rest of the troops were already in the

basement, five or six total of the battery personnel, no officers, no non-coms, just

ordinary privates and PFC’s. The Corporal and other PFC that were carrying the

grenades with me had gone to the other side of the road, I never saw them

again.

Our plan, of course, was to try to hide out in the basement hoping that the

Germans would go by. Unfortunately, the bazooka had gotten their attention and

they knew we were there. Pretty soon the tank was at the basement windows

and within seconds the door to the basement was thrown open and a voice

yelled “Raush”, meaning “Get Out”. We came upstairs and were met by the

troops of the First SS Panzer Corps. These were young, but hardened tankers.

One strange thing I noted was, they didn’t have their helmets on, but

instead the helmets were attached to their belts. I noticed one German wearing

a bandage around his head, another with bandages on his arm, but they were

still fighting.

As we came up from the basement and walked along the wall of the

farmhouse, the young German soldiers stopped us and took our watches,

wallets, and anything of value they felt was the booty, the plunder of War. That is

where I lost my brother Bill’s Elgin watch that my mother had given to me before I

had gone into the service.

We were taken out to the road where the Tiger tanks and half-tracks were

parked. Shells from artillery were dropping around the area, apparently some

American artillery were dropping shells in this area knowing that the German

spearhead was passing through. Within a few short minutes they had a few of

my buddies up on the tanks. This was done as insurance that no American

troops would fire on these tanks as long as there were American soldiers sitting

on them. Then off they went to the heart of the village of Bulligen. I was left

there with just a few of my buddies alongside the road.

After just a short time the German soldiers started to march us back east

toward the town, which I now know, was Honsfeld in Belgium. If I recall correctly

there was only six or seven of us when we were taken prisoners.

As we got to Honsfeld we could see a battle had taken place and it

appeared it had been at night. As I looked at a cemetery on the left hand side of

the road there were frozen corpses behind the headstones. You could see that

they had fought, one guy at a headstone, another behind a headstone and there

they were frozen in the position they had been in just as they had been shot. It

was quite a grotesque picture. About the same time we could see several bodies

laying in the road, it was hard to even visualize these were bodies because so

many tanks and trucks had run over them…German tanks of course. The

corpses were like pancakes and the Germans made us march right over them.

We tried to detour around them but they said, “No, walk over them”.

Shortly thereafter we got into a group of prisoners from other units and we

were taken to a building, it reminded me of a big dance hall of some kind. As I

understood it, our troops had been using it as a respite from their foxhole duties.

They would bring them here for hot food and get them warm, their feet would be

freezing.

There were infantrymen; I would say that there were approximately 200

American GI’s as prisoners, in this room sitting on chairs in this theatre-like room

with a stage in front. In a short time a German Officer, I believed to be a Major,

got up on the stage and talked to us in perfect English. He told us that they were

going to interrogate some of us and that the Germans would only interrogate by

rank. That is, a German Major would interrogate an American Major, if there was

an American Major, Captain against Captain and so forth. As they called out our

rank we should identify ourselves by holding up our hands. Well, we did this and

as the German soldiers came down the aisle picking out the person they wanted

to interrogate, they took them out of the room, out through the wings of the stage.

They never brought these people back in again and by the time they got down to

my rank, PFC, we were a little bit concerned about what had happened to the

men that went out before us.

Nevertheless, I raised my hand and a young German soldier walked

down the aisle to me. He gave me “the glare” and I gave him the finger. Then,

because he had a Lugar pointed at me, I joined him as he led me into the wings

of the room opposite the stage. This young German soldier could speak very

good English. The first thing he did was shove the Lugar into my stomach and

with his other hand he pulled the dog tags off my neck. Of course, I didn’t have

any idea what he was about, although I did note as I looked at him, he did have

on some American clothing, parts of our uniforms. This really didn’t arouse any

suspicion and his questions were not of a military nature.

He looked at my dog tag; he could see what my name was. He could see

my serial number, which I was permitted to give him by the rules of war. On the

dog tag he was very concerned because I had put down on my dog tag my

nearest of kin was Mrs. William F. Foehringer and he just could not get the

grammatical connection between a Mrs. And William, he felt that that should

have been Mr. Or it should have been Mrs. Madeline Foehringer instead of Mrs.

Wm. Foehringer. That really seemed to bother him. He went on to ask

questions about my home life, what I did before the Army. He was interested in

my education, really and that was about all he asked about. It was not a very

thorough interrogation.

In this room, I could see all the Corporals, Sergeants and Officers that had

been taken out, they were just holding them there interrogating them. Note: I

learned after the war or when I returned home that they had used our dog tags

and clothing, etc. and impersonated American soldiers to infiltrate our lines and

cause confusion and havoc. Many of our soldiers were killed by these infiltrators.

When they were finished with our whole group, which must have been

twenty soldiers, they did return us to the room.

We were in this room all together when it became apparent that the

Americans were strafing and bombing the area by air. The Germans permitted

us to go down into the cellar of the building.

As I recall, it was a very cramped, very small room and we did not have

enough room for all of us to get down there and have room to lie out or even sit

down.

By now it was early evening and we had had nothing to eat or drink, but I

don’t think there was one of us that had any appetite. We were all concerned,

worried and scared of what was next. We didn’t know if our own planes were

going to bomb and kill us while we were prisoners.

The night passed and the next day they started marching us out. That

would have been the 18 th of December 1944.

They marched us for several days. The first day, the 18 th , we were

marching past rows and rows of German troops, tanks, half-tracks and horse-

drawn artillery, plus every imaginable type of German military equipment. The

Germans were very envious of our boots, our leather boots, there was a definite

leather shortage in Germany. They would knock down the prisoners, including

myself and try to steal or take our boots away from us…they succeeded. Thank

the good Lord, I had a small shoe size, 6 ½, which no German foot could fit into

so I kept my boots. My buddies weren’t so lucky; many of them had to walk in

stocking feet from then on. That was a harsh winter, it was very cold and there

was snow. Many of those men suffered frost bite and lost many of their toes. I

would imagine ‘til this day they are suffering from when they had to walk so many

days in their stocking feet.

I can recall the Germans feeding us very little on this trip. We were now

very hungry, it was really catching up with us. I remember running out into a

sugar beet field that had been turned over and you could see the beets. I didn’t

even know what the heck they were, they looked like rhubarb or turnips and I had

never seen a sugar beet in my life. I did know they were something we could eat

because other fellows had done this so I ran out into the field, grabbed some of

the sugar beets and ran back to the line…the Germans didn’t shoot me. I broke

up the sugar beets and handed the peices around to the rest of the guys as best

we could and lo and behold it was something that gave us energy, it gave us

sugar, gave us heat and gave me the strength to go on.

I don’t remember how many days we marched, but they finally got us into

boxcars and I say finally but I don’t know if that was good or bad. They packed

us so tightly into those box cars even after I organized the whole box car, guys

were fighting one another. There is nothing worse than being a prisoner of war,

not knowing whether you are going to have enough food to exist. We were

starving, rattled and locked in a box car, it wasn’t any fun at all. Having

everybody organized, we tried to see if we could sit down at the same time…it

was impossible, there just wasn’t enough room for all of us to sit down. This was

to be our home for several days.

I can recall one of the first nights after getting on, we were in a railroad

yard in a big city, it turned out the city was Bonn in Germany on the Rhine River.

The Allies, the British, were bombing the city of Bonn at night. You can imagine

us, like animals locked in these box cars waiting for the bombs to hit and they did

hit in back of us. Down the way, I don’t know how many cars behind us, the

carnage of dead and wounded were many. But again, thank the Good Lord, I

was spared.

When the Germans finally got us to where they wanted to take us which

happened to be Stammlager 13C in Hammelburg, Germany, it was somewhere

around the 27 th of December. I know it was after Christmas for sure but the

confusion, the suffering didn’t give us much time to think about what day it was.

We were just damn glad to be alive but I do recall how emaciated we were and I

remember then walking up the hill to the camp. It was something else, we were

exhausted, no food, very little water and it was quite a hill. Some guys didn’t

have shoes if you recall, the Germans had taken their shoes away from them and

they were walking in stocking feet. But at least we were out of the boxcars; we

weren’t locked up any more.

We were going to a prisoner of war camp and our minds were picturing

food, heat, a roof over our heads, clean clothes, all those things that went with

being back to the world of the living again.

As we got there I remember the gates were opened and in we walked.

Many of the guys had to be carried as they couldn’t make it on their own. We

were split up into small groups and led into a compound with a small one-story

frame hut much like the picture that you have seen in the movie of Stalag 13. It

was very primitive, no inside wash rooms, no running water, no central heat, just

bare essentials. Inside there were double-decked wood bunks, straw

mattresses, no blankets, very minimum living conditions.

The German guards were all eager to barter or trade anything that we

might have that they needed. The thing that seemed, as I recall, most

predominant was leather goods, wallets were one big bargaining item. We

wanted food and cigarettes from the Germans. I remember the wallet, because I

had kept my wallet. I didn’t have anything in it and the Germans weren’t

interested in what was in it, just in the leather itself. A guy in my outfit who was in

the next compound, with barbed wire separating us, a guy by the name of Ross,

he was from Kentucky or West Virginia. Ross was one of the guys that could

neither read or write, but could live by his wits and that’s what he did. He conned

me into giving him my wallet so that he could get a carton of cigarettes from the

German guard. Well, I gave him the wallet and never saw Ross again. This is

an example of life as a prisoner of war, it was dog eat dog. He knew I couldn’t

get to him thru that barbed wire to his separate compound, so he got away with

it.

The heating in the huts was from pot bellied coal stoves. Our food

consisted of black bread, which we had to divide one loaf for eight American

prisoners. It had to be minutely cut as one man couldn’t get more than another.

For a little change we would take our slice of bread and hold it against the pot

bellied stove, it was our method of toasting it instead of eating it plain.

I think I mentioned it earlier that I had torn my jacket going through the

hedgerow during the escape from the Tiger Tank coming down from that small

Belgian village. Well, one day they came into our compound and said we were

allowed to go through the clothing warehouse to get or replace clothes needed,

emergency clothes, if we could prove we needed them. All I had was a field

jacket and it was torn so they allowed me to go into the Red Cross warehouse

and pick out an overcoat. The overcoat was from the Belgian Army, it was quite

large. I don’t know whether I picked it out on purpose or not but it just about

reached the ground. Maybe there was a method in my madness, it was my

shelter, my warmth, whatever, anyway that was the way it turned out to be. This

and all other clothing was marked on the back with a large white PW, so we were

identified as Prisoners of War.

Another interesting thing that happened in this Stalag 13C, Hammelburg,

Germany was, when the Germans came into our compound and lined us up, they

asked for all the Jewish boys to step forward, assuring them that nothing would

happen to them if they volunteered to step forward. We all yelled at them not do

it, not to step forward, but I believe some did without thinking and needless to

say, we never saw them again. I had a friend of mine in my outfit, I think I’ve

mentioned him, Al Goldstein from Detroit, he did not volunteer and he later went

out to work in Germany in the same “arbeit command” (work group) that I was in.

There was another interesting thing that went on regard the Jewish

soldiers, it happened later.

I had diarrhea through the whole trip since becoming a prisoner, mainly

because of no food or improper food like those sugar beets. My underwear was

terrible, so one of the things I did was to go over to the water supply and wash it

best I could as there was no soap and I hung it out to dry, but this was in

January, it froze. I finally took them in and hung them by the stove. I felt

fortunate that I washed them when I did, as I never had a chance to do it again.

I guess, I mentioned that everyone in the compound was either a Private

or a PFC. The Germans were very strict on the mixing of the military ranks. All

privates and PFCs were kept together, all corporals and sergeants were together

and the Officers were all separate. So we were all Privates and PFCs in this

compound.

One day, after we had only been in camp a short time, I would say around

25 days, when the Germans came in and again lined us up and said that as

Privates and PFCs we could by Geneva Convention volunteer to go out to work

at non-military occupations. A number of us volunteered. I felt that any place

where I could keep moving was better than the monotony of doing nothing. Just

existing in a Prisoner of War Camp was not for me. A chance to get out and do

any type of work to keep my mind occupied would make the experience pass

quicker. All in all there were about 100 soldiers who volunteered to go out of the

camp.

One afternoon we marched down to the railway station in Hammelburg.

I’ll never forget this, there were several other people, civilians that were going to

take this train, passenger trains could only run at night, so we were waiting

around until twilight for the train to come in. When it did arrive, we were

surprised to see every other car was a flat car with an anti-aircraft gun mounted

on it, manned of course by German soldiers. The guns were an attempt to

protect the train from strafing and bombing by American or British planes.

We were quickly herded into the trains and were off though the German

countryside. We thought possibly we might be going to farms, but lo and behold

we stopped at what we took to be a pretty good-sized railroad station. They got

us off and we marched three or four miles out to what appeared to be a large

gym. This gym was in the midst of a bunch of high-rise warehouses in an

industrial district. Inside the building there was what looked like a big fountain. It

turned out to be a place where we were able to wash our face and hands as we

came and went. There were toilets too and there were double-decked wooden

bunks with the straw mattresses and I mean loose straw, not packed. This was

to be our home, for how long we didn’t know.

I took the upper bunk all the way at the far end of the building. I don’t

know why, but I remember not letting anyone take the bunk below me.

There was a doorway about twenty feet from my bunk, which I always

thought about. Several times the guard would catch me looking at the door, he

never said anything, he would just make sure I knew he was keeping a close eye

on me and that doorway. He was the only guard at night and the Germans knew

that was all that was needed. We were both physically and mentally rung out.

Any plan of escape or where to go if we did seemed out of the question at the

time.

I managed to sleep fairly well, but remember always being conscious of

the guard walking around the building all night, probably trying to keep himself

awake too.

Another Jewish fellow, Howie Wolf spoke Yiddish, close to German, and

became our interpreter. The Germans lined us up and used Howie to break us

down into individual work groups. I got to know him fairly well and I told him

when he heard of a good occupation give me the nod and I’d volunteer for it. So

several occupations were named off and guys were picked out, 10 here, 20

there. Finally they came to “a five men bakery”, he nodded to me, so I stepped

forward and volunteered and I’m glad I did.

This was a small detail with one guard, a Phillip Kraft, who picked us up

every morning and we were on the road to a small German military bakery.

Actually we worked in the warehouse of the bakery, which was on the second

floor. The only thing that we had to do with baking was to move sacks of flour

form one end of the warehouse to the other and my understanding of this was to

prevent infestation. Then periodically the bakers would bake huge amounts of

bread downstairs and they would back up a truck…a flat bed. The sides were

rolled-up canvas, you could either roll the canvas down and be enclosed in there

or leave them open and it would be an open sided truck. An interesting part of

this vehicle, in the back it had a hot water tank with a little furnace at the bottom.

In the furnace they would burn wood chips. They had burlap sacks filled with

chips, maybe three or four on each truck. The German didn’t have oil or gas like

we had so they ran the truck by steam. Every once in a while the driver would

get out and throw more chips into the little stove or furnace below the water tank,

it was quite interesting.

Getting back to the bread…we’d make a human chain and throw the

loaves of bread onto the truck and pack them on the bed and then off to the

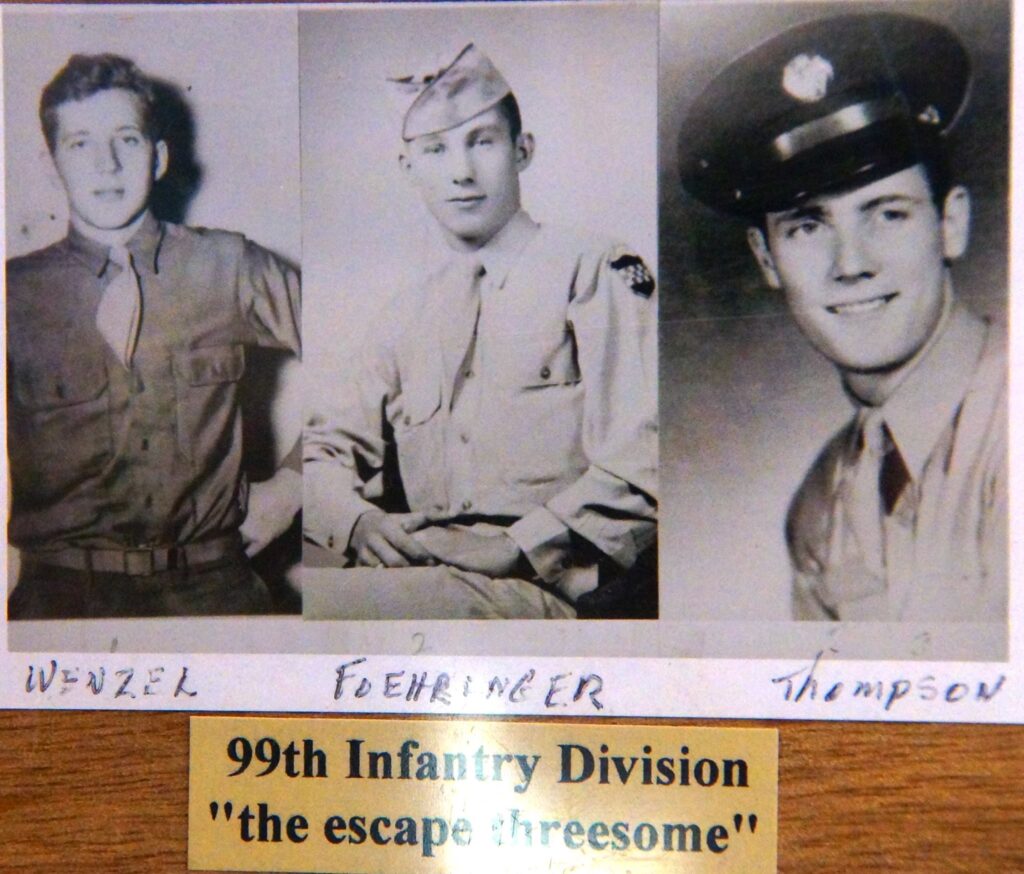

railroad yard we’d go, the driver, a guard and five of us prisoners. Howie Gilb

from Kentucky, Ray Wenzel from Stevens Point, Wisconsin, Don Thompson from

Melrose, Massachusetts, Howie Wolf and myself were the five guys in this work

group.

We pulled up to the box car that was assigned to us and filled the bottom

of the box car with straw and again we’d make another human chain and throw

the bread from one to the other then place it on the floor of the box car and

empty the truck out.

This one day the guard said to me and another guy, “Hey, you stay behind

and watch the bread because we have to go back and fill up the truck and we

don’t want anyone to steal the bread while we are gone.” Well, my buddy and I

said, “OK”.

There was a tavern across the street from the rail yard and the Germans

used to pay us every month in Marks and Pfennings, so we had some money in

our pockets. We understood from the Germans that everything was being

rationed in Germany except for two things, matches and beer. We were also told

that though the beer was not rationed, the taverns used to run out of beer quite

often. We saw the Germans walking in and out of the tavern or beer hall, as I’m

sure they called it, so we figured that there must be beer there. So across the

street we go and right up to the bar. It was an old-fashioned bar with the huge

handle for pouring the beer from the tap. We ordered up two beers and the guy

takes our money and starts to draw the beer. We are very apprehensive since

there was a big PW written on our backs and we were really concerned about

them finding us there, but nevertheless here we were ordering our beers.

All of a sudden we heard a loud whap and thought, they got us, they are

shooting at us, we turned to the side and here is an old German standing there

holding his beer stein. What he had done was to take a big blow to take the

foam off the top of his stein and when it hit the floor it had made a “whap”

sound…instead of a shot it was just the foam hitting the floor. We were so

relieved.

The bartender continued to draw our beers. Just as we got the beer up to

our mouths, we heard “Raus”. We turned around and there at the door was a

German guard with a rifle pointing right at us. Well, here we were caught and we

didn’t even get our beer. We might have had a little taste, but that’s all we had.

We had to put the steins down on the bar and get marched out.

Now that I think back on it there was no punishment, they didn’t do

anything to us for trying to have a beer. They probably figured it was a national

pastime and as long as we were in Germany we might as well try to join in the

national pastime, even though the guard didn’t let us drink it.

Another time I can recall being down in the railroad yard and we were

loading up the boxcars with the bread. Of course, this bread was going up to the

German soldiers, (I think I told you earlier that we were allowed to go out to work

in non-military occupations) we damn well knew this bread was going up to the

front. We looked down the line of railroad cars that were lined up with ours and

we saw these strange people loading other boxcars. The German guard told us

that they were “Ruskies” or Russians. We found that really interesting.

One day we had a little pause during the loading of the boxcar and the

guys delegated me to go down to the Russians, who were loading sides of beef.

There were women and men working together as prisoners. My buddies wanted

me to bum some cigarettes off these Russians. We understood that the

Russians didn’t belong to the Geneva Convention but through the Red Cross the

Germans used to give the Russians a ration of tobacco every month and if we hit

them right we could probably bum some cigarettes off them. So I walked down

and there was a big Russian guy and I told him, “cigarettes”. He said, “Yah” and

took a bag of loose tobacco out of his pocket and picked up some newspaper

that was lying there. He tore a piece of newspaper off the size of a cigarette

wrapper and handed it to me and told me to hold it or rather showed me how to

hold it, then he sprinkled the tobacco in the newspaper. We looked at each other

and he could tell that I never rolled a cigarette in my life, so he looked at me as if

to say, “You poor simple jerk, you never had to roll a cigarette” so he grabbed it

away, rolled it and handed it to me. I then asked him for matches and he lit the

thing up for me and as I puffed on it, walked back to my buddies. We passed

that homemade cigarette around and of course puffing as fast as we could

because we knew that newspaper burnt pretty fast. I can imagine somewhere in

Russia today there is an old Russian soldier saying, “Boy, you should have seen

the stupid American I met, he didn’t even know how to roll a cigarette, he didn’t

know what he was doing.”

So that’s pretty much what I did as a prisoner of war in the Arbeit

Commando in Wurzburg, that beautiful Bavarian city, on the Mainz River.

It was interesting to see how the Germans operated in this time when they

really didn’t have anything. Everyone was fighting and struggling to exist. We

were getting some of this information from our guard, Phillip Kraft and various

other Germans that we would meet here and there.

They didn’t have a heck of a lot of flour in this little bakery at any one time.

That warehouse was never anywhere near halfway filled. I can remember one

time when they ran low on flour, we drove in this little truck out to the countryside

to a mill. We met a group of Germans, four or five guys that were running this

flourmill. They saw that we were Americans and asked each of us where we

were from. I said Chicago and they made a noise like a machine gun, Al Capone

and gangsters. They also put their hands up to their faces, holding their noses,

because of the smell. What they were getting at were the stockyards. So they

were pretty well versed in what Chicago was all about. It was interesting to see

that they knew Chicago.

Day after day, seven days a week we did this. We were fortunate to have

a roof over our head so there wasn’t anything spectacular in what we did, our

little five man bakery work group.

There was an interesting thing that happened to Al Goldstein. He was

working in a larger group of twenty men in a warehouse and had been working

there a couple of months when apparently some American soldier tipped off the

Germans that Al was a Jew. Well, the Germans, even late in the war were not

friendly to the Jews. Al’s punishment for being a Jew was he still went to work

with the group but when he got to the warehouse they would put him down in the

bottom of the elevator shaft and he couldn’t get out of that shaft until nightfall.

His punishment was that he could not associate with anybody and had to stay in

the elevator shaft. This was in late March 1945. They really had a hate for the

Jewish people.

Al did get back safely to the States and lived in Detroit for a number of

years. Another good friend of his and mine by the name of Frank Garrett used to

get together with Al. Frank was a prisoner of war too and we were in the same

outfit, the 99 th Division. Goldstein didn’t suffer much more that we did, but I think

if he had been found out back in Hammelburg he would have been put to work in

the salt mines.

Wurzburg is a beautiful city, with the vineyards sitting up high on a

terraced hillside, it was quite a sight. There was also a very famous bridge,

although at the time that we were there we didn’t see it, but the bridge has all of

the Apostles, large statues at various positions on each side of the bridge going

across the river Mainz.

There were several hospitals in the town and at different times we did see

German Soldiers, amputees, walking around the area. A railroad center really,

that had never been touched by the war. The American or British had never

bombed it, so we saw it when it was untouched…But the day was coming.

Off and on, oh maybe every other day, we’d get air-raid sirens. There

would be an air-raid alert but the American planes were going over to Swinefurt

to bomb the ball-bearing factories, so in the early days we were not bombed. But

later we started to have air raids and they were bombing Wurzburg.

One day our guard, Phillip Kraft, picked us up at work and we talked him

in to cutting through the railroad yards home rather than the street. He was

reluctant to do it, nevertheless, the six of us, five prisoners and our guard with his

bicycle started to walk. A strange sound made us turn around and just above us

were P-38 U.S. fighters, three of them, making a strafing run. Again none of us

panicked, we dove under the box cars which were right next to us as the

machine gun bullets ricocheted off the tracks, but missed us and we weren’t

injured. So once again, God was on our side. It really taught us to never again

take a short cut through the railroad yards, beside our guard was not about to let

us try it again.

Phillip Kraft was a nice old guy who smoked cigars. We didn’t have any

tobacco, since we never saw any of the Red Cross packages all prisoners of war

were supposed to get. I take that back, every once in a while we’d see one on

the back of a civilian’s bike. Who knows they might have gotten them from

bombed out railroad cars, anyway we never got a Red Cross package. But

Phillip used to smoke cigars as I said and one day he came to work to picked us

up and take us to work. When we got the bakery he took us to the boiler room of

the bakery and he had wrapped up inside a newspaper, cigar butts that he had

saved, tiny butts, an inch long at the most. We were all smokers and tobacco

starved, so what we did was brake all the butts up and make it into shreds and

then rolled cigarettes from newspapers. We got quite a number of cigarettes out

of that. The cigarettes were quite strong, but anything was better than nothing.

So I think his heart was in the right place and I’m sure he felt sorry for us.

By the way, Wurzburg, the area that we were in was Bavaria, southern

Germany and the majority of the people were Catholic. There were many big

Catholic churches in Wurzburg that we walked by as we were going to work we

passed a company or two of Hungarian soldiers, Umguards, who were marching

to church on a Sunday morning. We were never allowed to go to church. We

worked seven days a week, we passed by them but never went in them.

As you can probably guess there was never a dull moment, that’s why I

wanted out of that Camp back at Hammelburg. This way, working, there was

some excitement and change. On our way back and forth from work, unusual

things would happen. We’d pass a group of Italians and we’d yell, “Yeah Pisons”

and they would yell “Yeah Comrade”. And, of course, we were always bumming

and begging and we’d say “Cigarettens” and they never seemed to have any and

we couldn’t bum anything off them.

One time we saw at the loading dock of the bakery, these two young boys,

I think they were bringing sacks of flour to the place. They would dump their flour

off on the loading dock and never tell us about it. We’d have to go down there

and check and this one time we got talking to these young boys and discovered

that they were Dutch prisoners that were in a work group. The Germans had

captured them in Holland and brought them back to make them work for them.

Of course, that is what Hitler did, he had hundreds of thousands of non-Germans

working for him at all kinds of jobs, including soldiering.

Then there was the time we met a group of Polish boys that were forced

laborers somewhere around our age, eighteen, nineteen, twenty, it was so

difficult to communicate with one another but we had a heck of a time trying with

no real time to learn. But they knew that we were Americans and we knew that

they were Dutch or Polish. It made an interesting passing of the days.

As we were getting around, walking back and forth through town, I’m sure

the German people knew that there were the Americans in town.

We’d meet little first and second graders coming from school and they

were practicing their English, as they were taking English in these lower grades.

They’d say “Good Morning, Sir” and we’d say “Good Morning” back and they

thought that was a lot of fun. We enjoyed it too, it broke up the monotony.

It was pleasant in Wurzburg and I say pleasant because we were not

particularly happy, but we knew that the war was going our way and knew it

would be ending. But this beautiful city of 100,000 people was soon to be

blitzkreiged by bombings.

One night, I’d say it had to be about the 20 th of March we were all in our

barracks sound asleep. Many times, by the way, when we did have air raids at

night and we were in the barracks, the Germans would get us up and we’d go

down into the sub-basement of this old warehouse, a six or eight story building,

which would be our air raid shelter. But this particular night, late in March 1945,

the British came over and night bombed. (By the way we always knew who

bombed us at night, it was always the British. The Americans bombed in the

daytime.) So we were “raused” out of our barracks and you know a lot of the

times the guys wouldn’t pay attention, they’d stay behind and wouldn’t go down

to the shelter because the raids would turn out to be false or the planes were

going by us or minor raids and they wouldn’t affect us.

Most of us went down this time and we weren’t down there too long when

pretty soon the Germans wanted to get us out of there. As we came out we

could smell the smoke. Well, when we got upstairs to the street level in this

industrial district, there was the most tremendous wind you have ever felt in your

life. The whole sky, the whole city of Wurzburg appeared to be in flames. The

wind had been created by the fire.

Lying on the street all around us were these phosphorus incendiary

bombs, they were octagon shaped bombs about a foot to maybe 18 inches long

and an inch or two thick. The bombs had hit the roofs of the buildings throughout

Wurzburg and set them on fire and that as we looked out was what we were

seeing, an inferno that the phosphorus bombs had caused. We were just

flabbergasted, but the Germans ran us out to the main road and further out of

town. In fact, they took us out to a farmyard. In the center of the farmyard, a

farm field, I should say, was a huge haystack and that proved to be our barracks

the rest of the time we were under the control of the Germans.

Back to Wurzburg and the inferno, I had never been through a fire like that

and I’m sure very few people have. It was just terrible. Well, they got us to this

farm yard and the next day they marched us down to downtown Wurzburg. I

couldn’t believe the devastation. What had happened was that these

phosphorous bombs had landed on the roofs and burnt down through the roof,

down the floors of the buildings leaving the walls standing. You’d have just a

shell of a building. And just like us, many people had used the basements and

sub-basements as air–raid shelters. Well, they were dead and by the time we

got there our job was to remove the debris and get the dead out of there. We’d

lift the bodies out and carry them to the curb and horse drawn carts would come

along and we’d pile the dead bodies on them. They must have created a mass

grave for these people, I don’t know where.

That was our duty for two or three days, after the air raid, we did nothing

but go downtown to Wurzburg and help clean up the debris and carry away the

dead bodies. Of course, all the services, like sewer, water, gas and electricity

were all wiped out.

We were working right down town Wurzburg, right off the city square,

when one day in roared three big semi’s. They let the sides of the trailers go

down and they were kitchens, they were called, “Herman Goring” kitchens. They

had stoves for cooking and they made soup and bread and whatever they were

going to feed the people in the city, and the people working down there. We saw

these folks getting in line to get fed, so we got in line also, anytime we saw food

we were ready and willing, but as we stood in line, all of a sudden things came to

a roaring stop. They wouldn’t feed anyone, we looked around and here were a

half a dozen or so SS Black uniform soldiers, Storm Troopers, they were called.

They gathered the whole crowd around us and made us the center of attention,

ranting and raving then pointing. These people were getting irritated and upset

and it was a foregone conclusion as to what they were trying to do. They were

trying to pin these air raids on us, but the Germans knew that the English

bombed at night, not the Americans. We yelled out, “Nix Americaners, English”

and we kept yelling that out and you know they stopped and disbanded the

crowd then kicked us in the ass and told us to go on back to work. That was the

end of it, we thought for sure that was going to be the end of us.

As was mentioned before, Wurzburg was now being bombed on a regular

basis. Typically it was at night by the British.

One day the guards sent a group of prisoners to help clean up the rail yard

where boxcars had been hit. A couple of the guys found a case of socks and

smuggled them back into the compound. That night they handed them out to all

the rest of the guys. The socks we were wearing were in terrible shape after four

months of continuous use. This was like a piece of Heaven.

The next morning when the guards lined us up for the headcount, all of us

mange POWs fall out wearing brand new royal blue Luftwaffe socks. The

Germans had a fit, they ranted and screamed as only the Germans could. We

thought for awhile they were going to shoot us all, but it ended as fast as it

started. They just pushed us around a little and marched us off to our jobs.

They even let us keep the socks.

Over the next night or two you could see the sky lit up and we began to

hear rumbles and we knew the front was coming.

We were still cleaning up after the air raids in Wurzburg, when the

Germans decided on Easter Sunday, April 1 st , 1945, that they were going to

evacuate us and move us further back into Germany before the American troops

over ran us. By the way, I might mention we did suffer casualties through these

raids. We had several guys killed and wounded. So that from the original 100

that started in this “arbeit commando” I’d say there were about 80 left.

Of course, when they said, “Let’s go” we didn’t have to pack, everything

we owned we had in our pockets or on our backs. So off we went, they didn’t

take us on the main road out of town they took us on the side road parallel to the

main road, as that was being used by German troops and trucks and they didn’t

need us clogging it up.

They would give us breaks every so often and at one of these breaks, the

five of us guys that worked at the bakery decided that we were going to escape.

The next time they gave us a break we were each going to go up to a different

guard and tell them that we were going over to the woods to take a “shizen”.

So at the next stop or rest period, we did just that. We told them we were

going into the woods to go to the bathroom. We did this and just stayed there.

The rest of our group got up and walked away, leaving us behind and I don’t

know if they even knew we were gone, but they didn’t seem to care. Now all we

had to do was to hold out, as we knew that the Americans would over-run us

shortly.

Now the “Odyssey” begins…now what do we do? The first thing was try

to get closer to the front so we’d meet the Americans troops sooner. We couldn’t

do this during the day it could only be done at night. So we decided to stay right

where we were the rest of that day and night and let things calm down a little.

We heard troops moving on the road, we saw what we thought were SS men

moving about, opening sedans and getting out of their big Mercedes.

The next night we did move back towards Wurzburg, and not knowing the

territory, we moved down into a low area that was surrounded by what we

thought were willow trees along side a creek. We needed water so we stayed

there overnight. At least we were able to get the water out of the creek.

When we woke up in the morning, lo and behold, right above us looking

down upon us, were a group of German civilians, women and children. The

German woman had taken their children out of the city and out of the ‘dorfs’ of

Wurzburg so that they would not be in the air-raids. They would sit on the

hillsides and get out of the way of the war that was going on around them. They

could sure see us down below them and it looked like they were getting irritated

when we noticed them. I again volunteered to go up and try to calm them. I took

a little prayer book out of my pocket. I showed them the “Rosary” on the back of

the prayer book and I started to recite some of the Mass prayers in Latin. These

were words from the Confiteor, “Adeum quitifica”. Not knowing who we were or

what we were, but did know the big thing, that we were prisoners of war, as we

had PW stamped all over the backs of our clothing. My Latin words seemed to

calm them down. I left them and walked back down the hill to my four buddies

and reassured them that I felt that these women and children would not turn us

in.

It was just a short time later, maybe a half hour or so, while we were laying

on the ground, there along side the stream, that rifle shots were winging over our

heads and hitting the embankment behind us on the hillside. We just didn’t know

what to do. The women must have turned us in. It appeared, without taking a

vote that this would be a good time to turn ourselves in. Why get killed now, the

war was almost over. We knew the skies were lit up with explosions and we

could hear the advancing American Army. It was just a matter of hours really

and this thing was going to be over. So why take the chance of being killed. So

up we got and best we could we ran across to the main road there and started to

run into the small village ahead of us. I found out later, the village was a dorf by

the name of Versbach.

Now this was hilly country and as I looked up on the side of the hill, I could

see two elderly gentlemen waving with their arms at us, signaling for us to come

their way. We did a detour off the road and ran up the side of the hill, it was quite

a ways up to these two gentlemen. They had a hole in the side of the hill where

they had apparently had dug a cave. It was covered with a burlap sack. We

were pushed in or told to get into the back of the cave fast, which we did.

Someway or another we felt that the two elderly gentlemen were trying to save

us, not hurt us. We did, quite readily get into the cave.

We stayed in that cave until after it got dark before peering out. We were

well above the highway and could see cars and German equipment taking off

and moving away from the front. The fight was still going on but some of the

German troops were pulling out. In particularly it appeared to us the SS in their

open Mercedes-Benz cars went by us. They were going east so maybe they

weren’t in Wurzburg or in this small village, perhaps they had left, all of them,

which relieved us and we knew that they were the tough ones and knew that they

would cause us the most harm.

It was probably about eight or nine o’clock at night or maybe even later, I

forget when the sun set, it was quite late at this time of year, the Spring. Around

April 3 rd to the 5th, up came two young boys into the cave and brought with them

for us to eat and drink, black bread, lard and ersatz coffee (artificial coffee) and it

was hot. As you can imagine since we hadn’t had solid food in over three days,

we were very hungry. The boys fed us, then took the empty cups back with

them. We were unable to communicate with them verbally, they couldn’t speak

English and we couldn’t speak German, but we got from them through hand

signals that we should stay there and they would be back.

So the next day during the daylight we stayed right in cave. This was a

good place for us to hide out, wait for the Americans to come through and over

run us. And that’s what we were hoping and praying for.

We felt much better now, we felt somebody was helping us and we did get

some food. Somebody did care here. So again, the next night here comes the

two boys back again, with the swartz bread, black bread, the lard and the ersatz

coffee. And boy how we put that away. And they again told us to stay still, don’t

get out of there, they said stay in the cave and hide. That they would let us know

when to come out. So we stayed that night and all the next day and late in the

afternoon of the following day, here come the two boys and they were running up

to the cave yelling, “Amerikaners kome, Amerikaners kome,” yelling to us.

They were yelling this before they got to the cave and of course we heard

them and I recall Howie Gilb anxious and very eager as we all were, but he

wanted to rush out and we tried to caution him to watch out that it might be a

trap, there may be something wrong but Howie wouldn’t listen and out he went.

There wasn’t a trap; it was just the two boys there. They were very happy,

enthusiastic, jumping up and down anxious to tell us “Amerikaners kome,

Amerikaners kome”, and that they would take us down to the “Amerikaner”. So

we, all five of us, with the two boys in the lead raced down the hill towards the

little town square in Versbach.

The everyone from the little village (dorf) was surrounding a jeep which

was in the center of the square and on top of the hood of the jeep was an

American Sergeant waving a 45 around in the air. The crowd, the German

people made a path for us so that we could get to the jeep. The Sergeant came

down off the hood still waving his 45 around and began to talk to us. He told us

that the people had told him that they had hidden out some American soldiers

and that they would go and get them. They also said that they were so happy

that they did this, to show the Americans that they were not their enemy.

We told him, we were so glad that he came through and as we talked

further with him we asked him where his buddies were. We finally found out that

as happy as we were to see the Sergeant, the man was drunk. He told us that

he had been drinking and that he was a mechanic with a tank destroyer outfit in

the rear echelon. It seemed he got to drinking and decided he was going to go

up to the front to find out where his buddies were, the guys that drove the tank

destroyers. He had gotten lost, and apparently had just come through the lines

with the jeep. Nobody had bothered him, he had just gone right down the road

toward Wurzburg but he wanted to know which was the way out and how he

could get back.

Every jeep in the world had a foot locker and in the foot locker were all

kinds of paraphernalia, the main things that they kept in them were rations, candy

bars, “D” rations, “C” rations, “K” rations, plus all kinds of bandages and medical

equipment. Well, this jeep and this Sergeant was no different than any other and

we opened up the foot locker to get at some of his goodies, and then we realized

we should be giving some of these goodies to the German people who had

helped us, so that’s what we did. We took out cans and “K” bars and everything

that could be found in the foot locker and threw them to the people and let them

know how much we did appreciate what they had done, although we never did

get the names of the two German boys that came every night, we never did see

the two old grandfathers that put us into the cave again. Now isn’t that

something, here were people that really saved us by hiding us out and feeding us

and yet we didn’t even know their names.

We were just elated, you can imagine after spending many, many months

not knowing whether you were going to be alive from one day to the next, not

having food and here was an American soldier and he was going to take us back.

Yet this American soldier had been drinking pretty well and he didn’t know his

way back. So really, we had a decision to make, because the Germans were

very friendly to us we felt possibly we should stay with them and wait for the

troops to come. The Sergeant was really lost and had come thru the lines by

himself, but after a short debate, we decided that we’d all cram on this jeep,

imagine now there are six of us and we were hanging on the sides trying to go

thru the lines.

There wasn’t much to us, we had all lost so much weight. I was down to

100 lbs and I’m sure that the other guys had lost 50, 60 lbs or more, so that we

were about six hundred lbs between us. But anyway, we did climb on the jeep

and we turned around and got him on the highway.

We knew the way back to Wurzburg and as we started back we saw

burning German half-tracks, dead soldiers lying along side the road, but no sign

of our troops at all. There were no tanks or artillery, no firing going on but there

were plenty of signs that a battle had been going on here, but it all had stopped.

As we went on toward Wurzburg, along came a line of infantry on either

side of the road and of course it was an American infantry and on their helmets

was their insignias, this was the “Rainbow Division”, the old “42 nd Division”. Boy,

were we happy to see them. They were happy to see us and surprised,

expecting Germans before they saw Americans, a jeep with a bunch of

Americans hanging on the sides. After they saw us and saw how emaciated we

were they threw a million questions at us.

The Officer communicated by radio to his superior Officer and was told

that we were to be taken right down to the Commanding General. He had taken

over the city square of Wurzburg, so we were driven to the Commanding General

and he welcomed us back. The main thing he was interested in was, where had

we come from, had we seen any Germans, had we seen any build-up of anti-tank

guns or tanks in that area. In fact, we told them that we had seen the SS pull out

the day before. He was most thankful for this information and he was going to

send us back to the rear and he did.

First he wanted to have us examined to see we were all right. That was a

good thing because two of the guys were not feeling well. Howie Gilb and Don

Thompson, they had a fever and the medics thought that they had typhoid fever

from drinking the water out of the ditches. The other three of us showed no signs

of it so they took us about ten miles back into the area that they had already

taken, the other side of the Maintz River, to a small town where they had set up a

military government, with an officer and a squad of Infantry.

So here in this small town, we took over a house that still had running

water and electricity so we heated water and took baths. We washed and

scrubbed, there was just unbelievably filth and grime on us, as we hadn’t had a

shower or bath in six months. I had lice bites around the middle of my body that I

had scratched causing scabs on scabs, even in our hair, just everywhere on our

whole body. So we just soaked, the hotter the water, the better. I know I killed

the lice on me with soap and soaking.

The guys scrambled around and got us an issue of clothing. We were just